21 February 1980

(Inspired by an article of Hugh Moffet in an article in the Milwaukee Journal of February 20, 1980 Food Section).

I too am fairly well equipped to return into the “Old Days” of the Depression. There was little money for eight in the family so the diet was simple but robust.

Breakfast usually consisted of oatmeal (not the “quick” type but the old fashioned kind prepared in a double boiler. A great glob of the “koska” was sprinkled with brown sugar and soaked in milk (not the homogenized kind). If you were quick and sneaky you’d get the cream on the top of the mild before someone shook the bottle. Ah delicious, only it was so constant a breakfast I once had a nightmare with oatmeal the villain.

In those days we slept under feather beds (a big bag, bed-sized, filled with goose feathers). The feathers used to gang up at the foot of the bed and from time to time had to be beaten to the head. This was Ma’s job after we were asleep (two to a double bed). She did this one time and I awakened sometime later. My head was below the hump of feathers and I began to holler. Ma came rushing in to find out the trouble and I told her the room was filling up with koska and that it was already half full. Ma had saved me, but since that time koska is not my favorite breakfast food.

There was also home baked bread (always white) with butter, Ma’s bread didn’t ever come out too well, but her coffee cake (kuchen) was out of this world. Every Saturday she would mix and knead a tremendous pile of dough. It filled two big pans. These were put on the dining room radiator to rise. Once risen, she’d put it into big baking tins and again let it rise. Just before she put it into the oven she’d spoon melted butter on the tops and sprinkle sugar and cinnamon over it. Now and then she’d make a stroezel[?] topping. That kuchen would come out about a yard high and so tasty she’d forbid eating it until it cooled. So it lasted through the week and even at week’s end when it was hard it tasted great when dunked in coffee. No preservatives, as natural as can be and made with “three cents yeast”. The cake yeast, not the dry stuff

Another great meal consisted of potato pancakes sopping with maple syrup. These pancakes started out with spuds that were peeled and then grated. It took a whole big pan (the same pan Ma used for cake raising) full of potato mush mixed with eggs and whatever and then fried in a big cast iron skillet. Ma used two skillets to keep up with the demand at the table. The skillets held lard (not Crisco etc.) which had bits of bacon here and there (this added flavor but caused some consternation in Lent when meat was prohibited. Can you imagine “bits” of bacon being a problem? Anyhow the mush was spooned into the hot lard and it spread into all sort of shapes. When done the pancakes were a crispy brown on the edges and softish in the middle. They were the meal.

The same mixture of potatoes but a little stiffer went into a concoction called kluski or potato dumplings. Ma put a tremendous pot (gropa) of water on the stove to boil. While it was heating Ma would mix the “dough” adding bacon chips and bits of onion. With the water boiling she’d move the pan over to the stove and begin to drop tablespoon size dumps of the dough into the water. This took some time but when it was all done the pot contained a grayish ----soup with globs of cooked “kluski”. Delicious! Especially in the big soup dishes we had. These had a bowl with a big rim (we called ‘em sideboards). It was too bad we didn’t have kluski more often. The reason was that volunteers to “scrub” the potatoes were scarce and only reluctantly came forth. Why? Well grating or scrubbing spuds on that grinder “always” gave you skinned knuckles because Ma insisted that even the little nibbles of potato be used and that put your knuckles right on the sharp metal. Nobody ever thought we were cannibals because we ate the bits of knuckle that dropped into the mix.

Another cheap meal that no longer is around is sauerkraut and spareribs. Again the big kettle, into which water, then spareribs, then barley and finally sauerkraut were placed was the water. Once done (whenever that was) the steaming mixture was heaped into serving bowls and set on the table (covered with red and white oilcloth another victim of “progress”) and in turn spooned out on individual plates. The aroma remembered can’t be “explained”. The kraut was eaten with a fork but the ribs which most often broke apart in the cooking, were fingered. There wasn’t too much meat but the bones were soft enough to crunch. Only my sister, Bernice admitted she liked the bones and to this day makes much of her taste for bones. ---I believe is an attempt to “be different” since she wears double dentures. Anyway spareribs today are merely bones and expensive and usually end up having grilled on smoky backyard grills. Not so in the beginning.

The kraut was home made too. Ma and her friend Monica, Mrs. McK----[?] we called her, would spend hours shredding cabbage on a two blade kraut cutter. This gadget (there are two in the house — one is the genuine) had a sliding open box which held the cabbage which was then passed over the blades and then fell into an earthen ware crock below. Periodically handfuls of salt were thrown over the shreds and the process would go on until the crock was full. Then a board or two or and old plate were put on top and a big fieldstone put on top. As the weeks went by the cabbage mix would cure amid gurgling and stink and eventually end up as kraut. We kids rarely got in on the cutting because it was dangerous. The kraut tasted better to us as a result.

Kippered herring (schledge?) in ten pound wooden kegs are also a bygone treat. As Lent approached, Ma would get a keg and have it handy in the basement. When a meatless meal was in order (Wednesdays and Fridays under the old regs), she would break open the keg and remove some of the very salty herring. This was the day before the meal. She would soak the fish to desalt them and then slice them into chunks and put them in a dish of sauce made from (I think) vinegar, pepper (the round black ones) and lots of onions. A marvelous something to remember. Now and then during the holidays these herrings are available in supermarkets. Ma Bensch supposedly put them up (or down if you’re from New England) and strangely enough they they taste remarkably like Ma made them. I’m certainly mistaken though. Ma’s herring was the world’s best and will never again be produced - maybe imitated but no more than that.

Lent in olden times meant certain traditions were observed. Down South, Mardi Gras, but in Milwaukee among the Poles and their imitators, ShroveTuesday was “punchki” day. “ Punchki” resemble Bismarks but only barely. Punchki were made from kuchen dough. After the dough had risen, Ma would flatten the dough on a special board Pa had made for her. She would then take a drinking glass - not any glass but “that” one of the right size and begin to cut out circles of dough. She’d put the glass in flour then punch out a circle of dough. The little cakes were put on a dish towel (these were flour sacks ripped open and washed) on which was spread on the kitchen table with its oil cloth and allowed to rise.

Meanwhile Ma got the gropa ready for deep frying. She would load in lard — not steam and pressure rendered, but kettle-rendered by some farmer friend — and start the burner. By the time the lard was heated (she had some way of telling if it was hot enough (no thermometers then, maybe a sample of dough dropped in?). The doughnuts had risen to the size of tennis balls. One by one she carefully dropped these into the kettle of lard until the surface was covered. The dough as it fried would get a beautiful brown on the under side and Ma would turn them over for the other side to brown. The very aroma was nourishment. When Ma judged (---- ---test [?]) the punchki were done she’d lift them out with a fork (not tongs in those days) let them drain a bit and carry the lot over to the table. As they cooled a bit, she reloaded the kettle then returned to the table where she rolled each doughnut in a sugar cinnamon mixture or just sugar and set them aside for further cooling. After the first batch, her big job was keeping everybody away from those punchki. At supper time we feasted and by next morning only a few were left for the early birds. Thus Lent was off to an official start. Today the practice is now and then mentioned among old timers and the advertising crowd trying to cash in on a family and ethnic tradition. And sad to say they fail. Most old timers don’t bother any longer.

Christmas time in older days was also an adventure. Weeks before the day, Ma would have shopped for the presents, books coloring paints etc., and [would] have managed to sneak them into the house unseen and have hidden them for that day. But the spirit or fever of Christmas came with the baking that went on. Mostly cookies.

Ma baked the world’s most delicious oatmeal cookies. Her genius lay in the ingredients and how she put them together. There were nuts walnuts, pecans (the old thick shells ones) hazelnuts, almonds and (what were then called nigger toes) Brazil nuts. Being in the shell all the vast heap had to be cracked open and the meat set aside each nut in its own container. All the kids got in on this. Some (the smarties) cracked and the younger ones picked the shells clean. Ma watched to see that the nuts ended up in the dishes rather than in hungry bellies. There were raisins light and dark. These had little stems to be removed. An unappreciated chore. And currants everybody called little raisins and wondered about as part of the cookies to be.

Rolled oats in great gobs, butter, flour and who knows what else. All was piled here and there ready to be added at the proper time and only Ma knew when that was.

Again the big bread and cake pan came out and Ma would begin mixing. As each dish of nuts or what-all was added, the dough got thicker and harder to mix. After a while I got a chance to squeeze and push, but only after washing my hands at the kitchen sink. The bathroom was upstairs and we almost always, except in the morning, washed at the kitchen sink and dried hands and face on a roller towel fastened to the chimney nearby. When Ma declared the mixture just right, cookie making began. Pans were greased and tablespoonful were fingered off onto these pans. The oven being just right — again no thermometer, she would spit into the oven (while it was empty of course). If there was a quick sizzle the oven was hot enough. In and out went the cookies which had spread out to about 2-1/2 inches. Ma guarded them. The cookies were for Christmas two weeks away. We all got a warm cookie and Ma stored the rest in an old 50 pound lard tin. She covered this and stored the lot in the attic. The cookies got hard as rock but as time passed they softened to a monstrous tastiness. I know because from time to time I’d sample them being careful to rearrange the remainder so the pilfering wouldn’t be discovered. I shouldn’t have bothered. Ma knew cookies don’t shrink that much. Yet there were enough left. Christmas and Santa Claus came anyhow despite the bad mouthing Ma gave me, though I repeatedly declared my innocence and blamed mice for the foul deed. I never figured out that if mice got the cookies how would I know. Ma did.

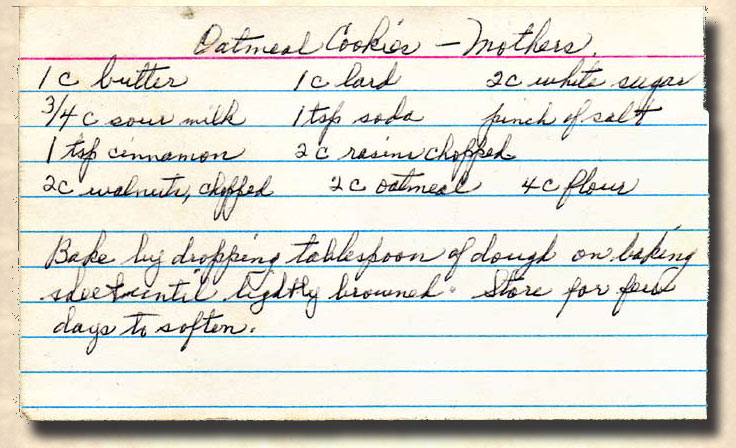

(Recipe written out by Aunt Bernice, Louie's oldest sister)

Supermarkets didn’t exist. Little stores were everywhere. There were five within three blocks of our house so shopping was different. Where today I go by car to a market once a week, then I would be sent for butter during the meal and be back before Pa had finished slicing the bread. No sliced bread for some time and the bread was a coarse textured rye bread. Tasty as no bread today ever pretends to be.

We used a lot of potatoes. The little store had a bushel always standing, but Ma bought potatoes directly from farmer friends who, in season, brought wagonloads (later on truckloads) into town and peddled them to perennial customers. Ma bought 12 bags of 100 pounds at one time. These were carried to the basement where Pa had built a big tight box big enough to fit. This box was in a back corner in the dark next to the coal bin. It had a hinged door in front that was locked in place when the box was loaded and could be dropped as the spuds were used up.

It was one of the terrifying things about that dark basement. Although we had electric lights, there were only three bulbs to light it and none near the potato bin. When sent for spuds after the top layers were gone, I had to lower the door and reach in for each spud. The lower the pile sank the more of me had to reach in. There is nothing to compare to the delicious terror felt with my body half in the black box reaching for elusive spuds and then dashing up the steps with “something” right behind me. This was bad enough but in the spring potatoes sprout and rot. The box had periodically to be cleaned up and the bad spuds removed. Imagine reaching full body into a black hole, reaching in and grabbing a gob of stinky gunk. The shock was terrible enough with a hand full of gunk but what of the other dangers? There were bogey men in there I swear it.

Ma also bought carrots in big bulk. These she put up in a sand filled crock. And cabbages too. When these went bad there was a real stink difficult to describe. It has to be experienced this grabbing stinky mush business. There were bags of onions too.

We canned some things, like pickles. Big pickles in vinegar juice and dill. Smaller pickles in slices and different juice. Finally the big guys who soaked in wash tubs, I don’t know how long, in water, salt and alum. Sweet sour they were called when finally packed. Real crunchy they were.

Tomatoes had to be peeled, then packed or canned in Mason jars with zinc tops set in red rubber rings that sometimes didn’t seal. And then “Chicago Hot” was concocted. Tomatoes were the main ingredient, green ones. These were ground by hand in a grinder fastened to a table. Guess who turned the crank? All sorts of things found their way into this mix. Horseradish was also tearfully ground up and canned. Who ate it I don’t know but just looking at a jar brought tears to the eye. That was horseradish I tell you. It neighed at you.

Ma kept chickens right in the back yard so eggs we had in plenty. Enough to sell to the neighbors at times. So we had no need to store them nor did we have more than an ice box to keep them cool. Some friends used to put eggs up in water glass. To do this, the eggs had to be chicken fresh and unwashed (you know what that meant). Whatever waterglass is, it had to be mixed, and the eggs put into it. The stuff looked like clear jello. Ma didn’t use it. Cold storage eggs were available but no housewife who could help it ever used them or did so in secret and embarrassment. Then too the chickens ended up on the table.

Though Ma’s garden was a riot of flowers all summer long, she also had a vegetable garden. Here onions, radishes, kohlrabi, and much lettuce kept us in fresh greens. In spots she had herbs of one kind or other. In fall she’d gather in seeds, put them in brown paper sacks and hang them from nails in the attic on rafters. She knew what they were but I doubt anyone else did. Come spring time and the bags and seeds would vanish into a new garden. There were even spearmint plants which gave off a pleasant odor and ended up in mint jelly. A cherry tree stood there too until Ma had Uncle Mike cut it down. I remember him as the shaky uncle. He had Parkinson and looked fierce to me.

Pa would get Ma boiling mad when she planted flowers. He’d call them weeds and when she served the greens he’d call them rabbit food. She’d cool off after blistering him in Polish and German.

21 February 1980 (Inspired by an article of Hugh Moffet in an article in the Milwaukee Journal of February 20, 1980 Food Section). I too am fairly well equipped to return into the “Old Days” of the Depression. There was little money for eight in the family so the diet was simple but robust. Breakfast usually consisted of oatmeal (not the “quick” type but the old fashioned kind prepared in a double boiler. A great glob of the “koska” was sprinkled with brown sugar and soaked in milk (not the homogenized kind). If you were quick and sneaky you’d get the cream on the top of the mild before someone shook the bottle. Ah delicious, only it was so constant a breakfast I once had a nightmare with oatmeal the villain. In those days we slept under feather beds (a big bag, bed-sized, filled with goose feathers). The feathers used to gang up at the foot of the bed and from time to time had to be beaten to the head. This was Ma’s job after we were asleep (two to a double bed). She did this one time and I awakened sometime later. My head was below the hump of feathers and I began to holler. Ma came rushing in to find out the trouble and I told her the room was filling up with koska and that it was already half full. Ma had saved me, but since that time koska is not my favorite breakfast food. There was also home baked bread (always white) with butter, Ma’s bread didn’t ever come out too well, but her coffee cake (kuchen) was out of this world. Every Saturday she would mix and knead a tremendous pile of dough. It filled two big pans. These were put on the dining room radiator to rise. Once risen, she’d put it into big baking tins and again let it rise. Just before she put it into the oven she’d spoon melted butter on the tops and sprinkle sugar and cinnamon over it. Now and then she’d make a stroezel[?] topping. That kuchen would come out about a yard high and so tasty she’d forbid eating it until it cooled. So it lasted through the week and even at week’s end when it was hard it tasted great when dunked in coffee. No preservatives, as natural as can be and made with “three cents yeast”. The cake yeast, not the dry stuff Another great meal consisted of potato pancakes sopping with maple syrup. These pancakes started out with spuds that were peeled and then grated. It took a whole big pan (the same pan Ma used for cake raising) full of potato mush mixed with eggs and whatever and then fried in a big cast iron skillet. Ma used two skillets to keep up with the demand at the table. The skillets held lard (not Crisco etc.) which had bits of bacon here and there (this added flavor but caused some consternation in Lent when meat was prohibited. Can you imagine “bits” of bacon being a problem? Anyhow the mush was spooned into the hot lard and it spread into all sort of shapes. When done the pancakes were a crispy brown on the edges and softish in the middle. They were the meal. The same mixture of potatoes but a little stiffer went into a concoction called kluski or potato dumplings. Ma put a tremendous pot (gropa) of water on the stove to boil. While it was heating Ma would mix the “dough” adding bacon chips and bits of onion. With the water boiling she’d move the pan over to the stove and begin to drop tablespoon size dumps of the dough into the water. This took some time but when it was all done the pot contained a grayish ----soup with globs of cooked “kluski”. Delicious! Especially in the big soup dishes we had. These had a bowl with a big rim (we called ‘em sideboards). It was too bad we didn’t have kluski more often. The reason was that volunteers to “scrub” the potatoes were scarce and only reluctantly came forth. Why? Well grating or scrubbing spuds on that grinder “always” gave you skinned knuckles because Ma insisted that even the little nibbles of potato be used and that put your knuckles right on the sharp metal. Nobody ever thought we were cannibals because we ate the bits of knuckle that dropped into the mix. Another cheap meal that no longer is around is sauerkraut and spareribs. Again the big kettle, into which water, then spareribs, then barley and finally sauerkraut were placed was the water. Once done (whenever that was) the steaming mixture was heaped into serving bowls and set on the table (covered with red and white oilcloth another victim of “progress”) and in turn spooned out on individual plates. The aroma remembered can’t be “explained”. The kraut was eaten with a fork but the ribs which most often broke apart in the cooking, were fingered. There wasn’t too much meat but the bones were soft enough to crunch. Only my sister, Bernice admitted she liked the bones and to this day makes much of her taste for bones. ---I believe is an attempt to “be different” since she wears double dentures. Anyway spareribs today are merely bones and expensive and usually end up having grilled on smoky backyard grills. Not so in the beginning. The kraut was home made too. Ma and her friend Monica, Mrs. McK----[?] we called her, would spend hours shredding cabbage on a two blade kraut cutter. This gadget (there are two in the house — one is the genuine) had a sliding open box which held the cabbage which was then passed over the blades and then fell into an earthen ware crock below. Periodically handfuls of salt were thrown over the shreds and the process would go on until the crock was full. Then a board or two or and old plate were put on top and a big fieldstone put on top. As the weeks went by the cabbage mix would cure amid gurgling and stink and eventually end up as kraut. We kids rarely got in on the cutting because it was dangerous. The kraut tasted better to us as a result. Kippered herring (schledge?) in ten pound wooden kegs are also a bygone treat. As Lent approached, Ma would get a keg and have it handy in the basement. When a meatless meal was in order (Wednesdays and Fridays under the old regs), she would break open the keg and remove some of the very salty herring. This was the day before the meal. She would soak the fish to desalt them and then slice them into chunks and put them in a dish of sauce made from (I think) vinegar, pepper (the round black ones) and lots of onions. A marvelous something to remember. Now and then during the holidays these herrings are available in supermarkets. Ma Bensch supposedly put them up (or down if you’re from New England) and strangely enough they they taste remarkably like Ma made them. I’m certainly mistaken though. Ma’s herring was the world’s best and will never again be produced - maybe imitated but no more than that. Lent in olden times meant certain traditions were observed. Down South, Mardi Gras, but in Milwaukee among the Poles and their imitators, ShroveTuesday was “punchki” day. “ Punchki” resemble Bismarks but only barely. Punchki were made from kuchen dough. After the dough had risen, Ma would flatten the dough on a special board Pa had made for her. She would then take a drinking glass - not any glass but “that” one of the right size and begin to cut out circles of dough. She’d put the glass in flour then punch out a circle of dough. The little cakes were put on a dish towel (these were flour sacks ripped open and washed) on which was spread on the kitchen table with its oil cloth and allowed to rise. Meanwhile Ma got the gropa ready for deep frying. She would load in lard — not steam and pressure rendered, but kettle-rendered by some farmer friend — and start the burner. By the time the lard was heated (she had some way of telling if it was hot enough (no thermometers then, maybe a sample of dough dropped in?). The doughnuts had risen to the size of tennis balls. One by one she carefully dropped these into the kettle of lard until the surface was covered. The dough as it fried would get a beautiful brown on the under side and Ma would turn them over for the other side to brown. The very aroma was nourishment. When Ma judged (---- ---test [?]) the punchki were done she’d lift them out with a fork (not tongs in those days) let them drain a bit and carry the lot over to the table. As they cooled a bit, she reloaded the kettle then returned to the table where she rolled each doughnut in a sugar cinnamon mixture or just sugar and set them aside for further cooling. After the first batch, her big job was keeping everybody away from those punchki. At supper time we feasted and by next morning only a few were left for the early birds. Thus Lent was off to an official start. Today the practice is now and then mentioned among old timers and the advertising crowd trying to cash in on a family and ethnic tradition. And sad to say they fail. Most old timers don’t bother any longer. Christmas time in older days was also an adventure. Weeks before the day, Ma would have shopped for the presents, books coloring paints etc., and [would] have managed to sneak them into the house unseen and have hidden them for that day. But the spirit or fever of Christmas came with the baking that went on. Mostly cookies. Ma baked the world’s most delicious oatmeal cookies. Her genius lay in the ingredients and how she put them together. There were nuts walnuts, pecans (the old thick shells ones) hazelnuts, almonds and (what were then called nigger toes) Brazil nuts. Being in the shell all the vast heap had to be cracked open and the meat set aside each nut in its own container. All the kids got in on this. Some (the smarties) cracked and the younger ones picked the shells clean. Ma watched to see that the nuts ended up in the dishes rather than in hungry bellies. There were raisins light and dark. These had little stems to be removed. An unappreciated chore. And currants everybody called little raisins and wondered about as part of the cookies to be. Rolled oats in great gobs, butter, flour and who knows what else. All was piled here and there ready to be added at the proper time and only Ma knew when that was. Again the big bread and cake pan came out and Ma would begin mixing. As each dish of nuts or what-all was added, the dough got thicker and harder to mix. After a while I got a chance to squeeze and push, but only after washing my hands at the kitchen sink. The bathroom was upstairs and we almost always, except in the morning, washed at the kitchen sink and dried hands and face on a roller towel fastened to the chimney nearby. When Ma declared the mixture just right, cookie making began. Pans were greased and tablespoonful were fingered off onto these pans. The oven being just right — again no thermometer, she would spit into the oven (while it was empty of course). If there was a quick sizzle the oven was hot enough. In and out went the cookies which had spread out to about 2-1/2 inches. Ma guarded them. The cookies were for Christmas two weeks away. We all got a warm cookie and Ma stored the rest in an old 50 pound lard tin. She covered this and stored the lot in the attic. The cookies got hard as rock but as time passed they softened to a monstrous tastiness. I know because from time to time I’d sample them being careful to rearrange the remainder so the pilfering wouldn’t be discovered. I shouldn’t have bothered. Ma knew cookies don’t shrink that much. Yet there were enough left. Christmas and Santa Claus came anyhow despite the bad mouthing Ma gave me, though I repeatedly declared my innocence and blamed mice for the foul deed. I never figured out that if mice got the cookies how would I know. Ma did.

(Recipe written out by Aunt Bernice, Louie's oldest sister) Supermarkets didn’t exist. Little stores were everywhere. There were five within three blocks of our house so shopping was different. Where today I go by car to a market once a week, then I would be sent for butter during the meal and be back before Pa had finished slicing the bread. No sliced bread for some time and the bread was a coarse textured rye bread. Tasty as no bread today ever pretends to be. We used a lot of potatoes. The little store had a bushel always standing, but Ma bought potatoes directly from farmer friends who, in season, brought wagonloads (later on truckloads) into town and peddled them to perennial customers. Ma bought 12 bags of 100 pounds at one time. These were carried to the basement where Pa had built a big tight box big enough to fit. This box was in a back corner in the dark next to the coal bin. It had a hinged door in front that was locked in place when the box was loaded and could be dropped as the spuds were used up. It was one of the terrifying things about that dark basement. Although we had electric lights, there were only three bulbs to light it and none near the potato bin. When sent for spuds after the top layers were gone, I had to lower the door and reach in for each spud. The lower the pile sank the more of me had to reach in. There is nothing to compare to the delicious terror felt with my body half in the black box reaching for elusive spuds and then dashing up the steps with “something” right behind me. This was bad enough but in the spring potatoes sprout and rot. The box had periodically to be cleaned up and the bad spuds removed. Imagine reaching full body into a black hole, reaching in and grabbing a gob of stinky gunk. The shock was terrible enough with a hand full of gunk but what of the other dangers? There were bogey men in there I swear it. Ma also bought carrots in big bulk. These she put up in a sand filled crock. And cabbages too. When these went bad there was a real stink difficult to describe. It has to be experienced this grabbing stinky mush business. There were bags of onions too. We canned some things, like pickles. Big pickles in vinegar juice and dill. Smaller pickles in slices and different juice. Finally the big guys who soaked in wash tubs, I don’t know how long, in water, salt and alum. Sweet sour they were called when finally packed. Real crunchy they were. Tomatoes had to be peeled, then packed or canned in Mason jars with zinc tops set in red rubber rings that sometimes didn’t seal. And then “Chicago Hot” was concocted. Tomatoes were the main ingredient, green ones. These were ground by hand in a grinder fastened to a table. Guess who turned the crank? All sorts of things found their way into this mix. Horseradish was also tearfully ground up and canned. Who ate it I don’t know but just looking at a jar brought tears to the eye. That was horseradish I tell you. It neighed at you. Ma kept chickens right in the back yard so eggs we had in plenty. Enough to sell to the neighbors at times. So we had no need to store them nor did we have more than an ice box to keep them cool. Some friends used to put eggs up in water glass. To do this, the eggs had to be chicken fresh and unwashed (you know what that meant). Whatever waterglass is, it had to be mixed, and the eggs put into it. The stuff looked like clear jello. Ma didn’t use it. Cold storage eggs were available but no housewife who could help it ever used them or did so in secret and embarrassment. Then too the chickens ended up on the table. Though Ma’s garden was a riot of flowers all summer long, she also had a vegetable garden. Here onions, radishes, kohlrabi, and much lettuce kept us in fresh greens. In spots she had herbs of one kind or other. In fall she’d gather in seeds, put them in brown paper sacks and hang them from nails in the attic on rafters. She knew what they were but I doubt anyone else did. Come spring time and the bags and seeds would vanish into a new garden. There were even spearmint plants which gave off a pleasant odor and ended up in mint jelly. A cherry tree stood there too until Ma had Uncle Mike cut it down. I remember him as the shaky uncle. He had Parkinson and looked fierce to me. Pa would get Ma boiling mad when she planted flowers. He’d call them weeds and when she served the greens he’d call them rabbit food. She’d cool off after blistering him in Polish and German. |

Comments?

lou@designcoalition.org

Comments?

lou@designcoalition.org