|

|||

Open House at Bay Shipbuilding |

|||

Gabe's apartment has a view of the shipyard across Sturgeon Bay. |

In the reverse direction, Gabe points out his apartment from the shipyard. |

||

| About 1,000 employees work at Bay Shipbuilding in Sturgeon Bay. Now owned by Italian firm Fincantieri, it is one of the oldest and largest shipyard on the Great Lakes, encompassing some 63 acres, with many buildings and drydocks. They design Lake-going ships and build them during the warm months. In the Winter, when ice restricts movement on the Lakes, ships come in for repair and refurbishing. | |||

Day & Lou/Bill arrive, and Gabe begins the tour. In the distance is "The Shop", the huge building in which the ship sections are fabricated. |

Inside The Shop, a large section of a ship is being fabricated |

||

At the rear of the photo: pre-assembled deck houses, waiting to be craned into place. |

A 40-ton section, the full width of the ship, being transported on a motorized, remote-controlled multi-wheeled carrier. |

||

|

(above) The graving dock, the only dry dock on the Great Lakes large enough to accommodate a 1,000 foot long ship. (left) Gabe introduces us to "Big Blue", the largest gantry crane on the Great Lakes. (below) The water-wash system that cleans the anchor chain and cools it against overheating from friction as it is dropped. |

||

Shell plate—bent steel plates for various sections of a (future) boat.

|

(left) Gabe describes the submergible dry dock and how it functions. |

||

From the bow of the barge Day has a view of the tug part of the almost-completed ATB—'Articulated Tug-and-Barge'—that Gabe was finishing working on. |

The tug has been tarped for painting. The 'stalk' is actually the control deck, tall so that it extends above the barge deck to afford a view over the entire length of the barge. |

||

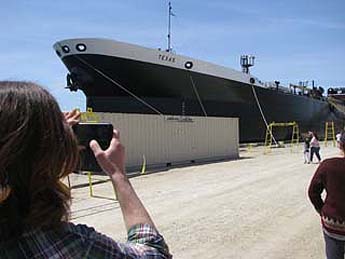

Although it has the appearance of a ship, the "Texas" is actually the barge, i.e., the non-motorized, cargo-carrying portion of the tug-barge combination. |

Overall view of the tug portion of the ATB—itself a 151 foot long navigable vessel—that contains the engine, control tower, and crew quarters. |

||

(below) Photo of a Bay Shipbuilding ATB on the water, showing the tug and barge combined.

|

|||

General view of the top deck of the barge—the valves and piping for off-loading and mixing the barge's liquid contents. This barge has a capacity of 185,000 barrels of oil, chemicals, or other petroleum products. |

Gabe points out the many valves and levers, alongside a modular cabin that he welded in place after it was craned, pre-assembled all-of-a-piece, onto the deck. |

||

Gabe looks down about 60 feet to the water level, at the aft peak of the articulation—the insertion point for the tug—at the rear of the barge. When tug and barge are fastened together, the ATB operates as a single vessel. |

View of the main deck. The catwalk at left runs the length of the barge, and raises the pipes to keep the deck clear for sailors to circulate conveniently. |

||

Overall view from Gabe's apartment window of the nearly assembled 700 foot-long ATB , |

|||

The next ship under construction…

|

|

||

|

(above) The inner-bottom, upside down here, showing the structural features of the ballast portion of the ship.

(above left) Photo showing the hollow interior cargo hold of the next boat. This section has been craned into the dry dock, ready to be welded to the previous section.

(left) Beginning fabrication of the bow section of the next boat in the queue. |

||

These photos show the teamwork of the many trades that contribute to the process of building massive modern cargo ships. Welders work most closely with fitters. Fitters assemble the shaped steel plates in the correct sequence and temporarily tack them together. Then welders take over, completing the assembly by permanently joining the pieces into a seamless whole. The Welding Samurai A Great Lakes ship is made with many miles of welds, and many are located at joints that are vital to the ship's structural integrity—and therefore to the life-safety of its crew, as well as protection of the cargo. Inspectors use x-ray and ultrasound devices to regularly test critical welds. Gabe has described some welds so long and so critical that welders will 'tag team', leap-frogging each other in hours-long stints creating a continuous, uninterrupted weld, in order to maintain the necessary metallurgical conditions at the arc location. If a weld fails inspection, typically it needs to be completely ground away and re-done, a laborious and costly error to fix and one that occurs with unfortunate frequency. |

|||

|

|||

Saving The Day Gabe recounted the story below, of the events of a certain morning which he only heard later; we've added the dialog of course, to bring the tale to life. Gabe and dozens of his crew had spent the days before and all that Spring morning readying a refurbished ship to hand back over to its owners. Workers removed tons of equipment and tools, welding machines, cables, ropes, scaffolding, ladders and the like that had accumulated. The 800 feet long ship floated in the now-flooded dry dock. It had required months, and millions of dollars in labor and materials, to accomplish the re-fit. And with that work completed, Gabe and most of his fellow teammates had already moved on to different projects elsewhere in the shipyard. An assorted crowd of people now stood on the dock near the gangplank: representatives of the ship's owner, some Fincantieri brass from Italy, Bay Shipbuilding's lead project manager, the crew foreman with some crew, plus the ship's captain and his own crew of sailors all with their luggage. The latter had arrived earlier in the week from various parts of the globe and were staying in a local hotel in anticipation of the turnover date—a date that surely involved substantial contractual penalties for late delivery. This morning all were anxious to get the newly repaired ship back into service on the Great Lakes. The diverse group cooled their heels on the dock while the inspectors were finishing their final check-off runs through the ship. Some Bay Ship workers were clearing away the last of their tools and equipment, and everyone else stood watching and waiting. It was one of those "This-Is-Costing-Somebody-Thousands-Of-Dollars-Per-Minute" moments. Finally, an inspector approached the group. The ship was ready to hand over—except for one problem: they had discovered, in between two of the huge cargo compartments deep below the waterline, a questionable section of bulkhead near the keel. It was only partially rusted, but they deemed it both a structural issue and a safety concern. They would not release the ship until the defect was repaired. You can imagine the alarmed—and expensive—consternation. The sailors stared in confusion. The ship's captain turned to the owner's rep, who turned to the Fincantieri brass, who turned to the project manager. He turned to the foreman and said, "Is this possible to reach? Everything's gone, scaffolding, everything. How do we fix this? Not sometime later this week—like, now?" The foreman took some silent moments to process. Then he turned to his crew and started issuing orders. "We need a welding machine back here pronto". He specified the proper unit. "We can winch it down into the hold on a rope. Slide it down the side. Power cable too." Workers ran for a forklift to fetch the equipment. "We need a plate" he said, specifying the dimensions and thickness. "Weld on some loops. Get rope to lower that down too. And a grinder and clamps." More crew sprang into action. Finally, turning to the remaining crew he said, "We've got one shot at this. We need a body harness and some climbing rope. And someone find Gabe."

Gabe arrived as the welding machine and steel were being readied to lower into the ship's hold. On the deck, the crowd gathered around the hatch to watch as he worked alone far below, maneuvering into position the heavy steel plate the size of a sheet of plywood, and welding its perimeter to the bulkhead. Gabe said the job took under an hour. The inspector passed the repair, hands were shaken, and the captain and sailors were cleared to board. |

|||

Gabe and Bay Shipbuilding on PBS |

|||

|

|||

Comments? lou@designcoalition.org

Comments? lou@designcoalition.org